Subscribe to the Interacoustics Academy newsletter for updates and priority access to online events

Training in Functional Assessment and Rehab

Motor Control Test (MCT)

Description

Table of contents

- What is the Motor Control Test (MCT)?

- Which reflexes does the MCT assess?

- Who should you assess using the MCT?

- MCT procedure

- MCT results

- Clinical applications of the MCT

What is the Motor Control Test (MCT)?

The MCT is designed to quantitatively assess a patient’s automatic postural response to an unexpected movement, otherwise known as a perturbation. It is performed using a dynamic posturography force plate.

In the test, a force plate will produce a translational movement stimulus in both the forward and backward directions at different amplitudes. During these translations, an automatic postural response should be generated by the patient. The posturography force plate will analyze and quantify this response and compare it against a set of normative data.

The results of the test can provide an objective assessment on how a patient’s automatic postural control system is functioning. It can reveal if the reflexes from the brainstem and spinal cord are creating automatic responses in a coordinated pattern [1].

It can also provide insights into the body’s strategy for responding to perturbations. This is essential knowledge when creating rehabilitation programs to ensure a personalized rehabilitation strategy.

Lastly, you can use the MCT as a follow-up tool to re-assess the patient’s functional status and progression in therapy with objective data.

Which reflexes does the MCT assess?

There is a hierarchical relationship in motor control made up of the following reflexes and responses.

Stretch reflexes

This starts with the quickest and most basic form of motor control reflex – the stretch reflexes. These are very fast reflexes with a latency of 35 to 40 milliseconds.

Because of their speed, they take place without the involvement of the central nervous system and instead are composed of the reflex arc with an integration center located in the spinal cord [2].

Automatic postural reflexes

The second set of motor control reflexes are the automatic postural reflexes. These come from the brainstem and produce coordination movement patterns. Because of their high integration center, these reflexes are slightly slower but still fast with a latency of 90 to 100 milliseconds [2].

As these reflexes produce movements that are more coordinated than the stretch reflexes, they form the first line of the balance system’s defense against perturbations.

The MCT is a measure of the automatic postural reflexes.

Voluntary motor responses

Lastly, we have the voluntary motor responses. These responses come from the brain and produce intended, coordinated movements. These have a latency of above 200 milliseconds [2].

Who should you assess using the MCT?

You can test any adult patient with balance or functional deficits, including instability or dizziness symptoms, with the MCT. You can use it to assess patients with weights up to 200 kg. If the patient is unable to stand still and unsupported, then this test is not recommended.

MCT procedure

The MCT is made up of two different force plate movements. These are backward and forward translations at various amplitudes. The test traditionally consists of three trials for each amplitude in each direction.

Typically, testing begins with backward force plate movements. You should complete the trials at randomized intervals to prevent a learning effect.

Before testing, you should perform the following steps:

- Enter the patient’s age and height into the system for correct force plate amplitudes and comparison to normative data.

- Patients should have shoes removed (barefoot or in socks) to allow for standardized input of the somatosensory system.

- Center the patient's feet on the force plate. The front edge of the medial malleolus of each foot should be directly centered on the horizontal line of the force platform. The outer edge of the foot should be aligned with the antero-posterior lines (Figure 1).

- Patient’s arms at side of body (Figure 2).

Once the test begins, the force plate will move backward in small, medium and large amplitudes. A normal response would be for the patient to have a quick, equal and opposite response at their ankles. The force plate position will reset between trials.

Like the backward force plate movement, the force plate will then move forward in small, medium and large amplitudes.

You can watch a video of the MCT being performed below.

MCT results

Following the MCT, the postural control responses from the patient are extracted. A report is generated for latency, weight symmetry, and amplitude scaling.

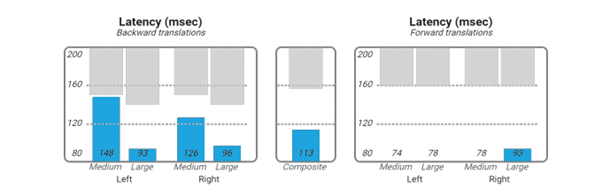

Latency

Measured in milliseconds, latency refers to the duration it takes for the automatic postural response to initiate after the force plate begins to move. Prolonged latencies suggest dysfunction in one or more components of the automatic motor system. This is often linked to lesions in the central and/or peripheral nervous systems [3].

It is important to note that age can have an impact on latency and therefore, having the patient’s age in the system is essential [4].

Although measured, the small amplitude translations are not used for calculations as we would not expect a need for the individual to react to a small perturbation. These translations are mainly used for familiarizing the patient with the test.

The postural responses to the medium and large translations are then analyzed. A normal latency for medium and large amplitudes is denoted by a blue bar in the white area on the graph below (Figure 3).

If the response falls within the grey area, the bar will be orange and indicates a long-latency reaction. The composite score is the average of all 12 trials and is useful as there can be artifacts in single runs (medium and large translations in the forward and backward directions).

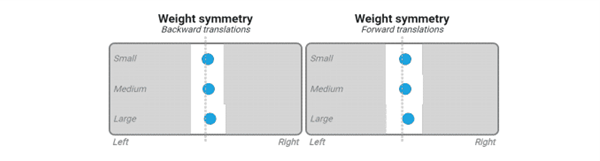

Weight symmetry

Weight symmetry measures the percentage of body weight that is placed on each individual leg during the test. Graphic representation of how the individual holds their weight, relative to right and left legs, for each trial is shown below (Figure 4).

Again, white denotes the normative data range. A blue dot represents a normal value. An orange dot represents an abnormal value.

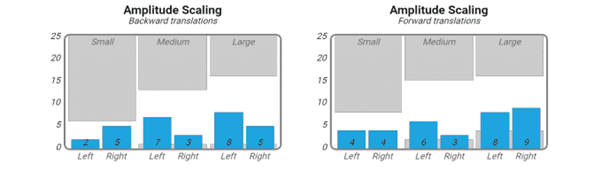

Amplitude scaling

Amplitude scaling refers to the strength of the postural response. It is denoted by a numerical value that represents how much force the individual had to produce to bring their body back to neutral position.

A normal response is for the amplitude value to increase in relation to the translation size and the responses should be symmetric between the left and right sides. Again, the normative data ranges are shown below with a blue bar in the white area (Figure 5).

It is important to recognize that amplitude scaling can be abnormally low, indicating an underreaction to the translation, or abnormally high, indicating an overreaction to the translation.

Underreactions usually occur in those with peripheral neuropathy or vascular disorders [5]. Overreactions can occur in those who are hypersensitive to the translation and are often seen in patients who are overly anxious.

Clinical applications of the MCT

The MCT is one assessment of the three Computerized Dynamic Posturography (CDP) assessments:

- MCT

- Adaptation Test (ADT)

- Sensory Organization Test (SOT)

It is important to perform all three assessments for a comprehensive picture of your patient with a balance disorder. Remember, these assessments are not diagnostic but can help you decide if you need to refer for additional testing and how to personalize your patient’s training program.

Below are some clinical indications that you can take from the MCT assessment.

Falls risk

Determine if your patient is at an increased risk for falls. If they have abnormal MCT results, they are at a high falls risk. Training is needed in these individuals.

Peripheral vs central impairments

An assessment of the reaction time latencies helps to assess this.

If reaction times are delayed bilaterally, this is more indicative of a central dysfunction. If reaction times are delayed unilaterally, this is more indicative of a peripheral dysfunction.

There are exceptions and it is important to pair findings with the overall clinical examination of your patient.

Functional responses

You can use the scores on the amplitude scaling responses to help assess this.

If there is an increased amplitude bilaterally, this can be indicative of an overreaction to perturbations. If there is an increased amplitude unilaterally or decreased amplitude bilaterally, these are more indicative of an orthopedic or peripheral nervous system disorder.

References

[1] Schwartz A. B. (2016). Movement: How the Brain Communicates with the World. Cell, 164(6), 1122–1135.

[2] McMahon, T. A. (1984). Muscles, Reflexes, and Locomotion. Princeton University Press.

[3] Di Nardo, W., Ghirlanda, G., Cercone, S., Pitocco, D., Soponara, C., Cosenza, A., Paludetti, G., Di Leo, M. A., & Galli, I. (1999). The use of dynamic posturography to detect neurosensorial disorder in IDDM without clinical neuropathy. Journal of diabetes and its complications, 13(2), 79–85.

[4] Olchowik, G., Tomaszewski, M., Olejarz, P., Warchoł, J., & Różańska-Boczula, M. (2014). The effect of height and BMI on computer dynamic posturography parameters in women. Acta of bioengineering and biomechanics, 16(4), 53–58.

[5] Vanicek, N., King, S. A., Gohil, R., Chetter, I. C., & Coughlin, P. A. (2013). Computerized dynamic posturography for postural control assessment in patients with intermittent claudication. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE, (82), e51077.

Presenter

Get priority access to training

Sign up to the Interacoustics Academy newsletter to be the first to hear about our latest updates and get priority access to our online events.

By signing up, I accept to receive newsletter e-mails from Interacoustics. I can withdraw my consent at any time by using the ‘unsubscribe’-function included in each e-mail.

Click here and read our privacy notice, if you want to know more about how we treat and protect your personal data.